“Emotional vs Functional Jobs: The Basics of Messaging” – Anthony Ulwick

Tony Ulwick is the pioneer of jobs-to-be-done theory, the inventor of the Outcome-Driven Innovation® (ODI) process, and the founder of the strategy and innovation consulting firm Strategyn. He is the author of Jobs to be Done: Theory to Practice (IDEA BITE PRESS) and numerous articles in Harvard Business Review and Sloan Management Review.

Tony Ulwick is the pioneer of jobs-to-be-done theory, the inventor of the Outcome-Driven Innovation® (ODI) process, and the founder of the strategy and innovation consulting firm Strategyn. He is the author of Jobs to be Done: Theory to Practice (IDEA BITE PRESS) and numerous articles in Harvard Business Review and Sloan Management Review.

Before devising a new messaging strategy, it is best to evaluate your current strategy and determine exactly where and why the current messaging strategy is ineffective. After a company has determined that a current product does address one or more underserved outcomes successfully, all that is left to do is devise a message that communicates that unique product value to the customer.

Companies often feel the need to appeal to their customers’ emotions, but depending on the functional and emotional complexity of the product or service being delivered, doing so can have unexpected and unwanted results.

A historical case worth studying is Motorola’s cell phone division. With Nokia breathing down their necks, management feared that Motorola’s products were no longer exciting people and felt their messaging and marketing campaigns were failing to capture the public’s imagination. They decided to bring in marketing experts trained by some of the world’s leading marketing companies, including Procter & Gamble and Pepsi. These experts quickly realized that Motorola’s products had no emotional appeal, and went to work with their makeover: they introduced a number of cell phone products branded with names such as Accompli (for those who want to be on the cutting edge), Vdot (for those who want to feel important), Timeport (for those who want to feel productive), and Talkabout (for those who want to feel in close contact with loved ones). Each brand was supposed to appeal to the unique emotional sensibilities of different segments of cell phone buyers. Years later, the strategy was abandoned for lack of results.

What went wrong?

It appears that when a company like Motorola that produces highly functional products tries to take a page from the Procter & Gamble playbook and adopts emotional branding, it will surely fail. Only when all or most of the needed function was delivered would it be worth considering differentiation along an emotional dimension.

In the years we have spent analyzing the vagaries of marketing, we have found that certain products – those in the cosmetic and perfume industries – are relatively simple, functionally speaking and are often purchased to help customers get emotional jobs done (such as feeling attractive to others). Products such as these need only satisfy maybe a dozen or so customer outcomes.

Perfume need only satisfy outcomes related to scent, strength, bottle shape, and packaging. As the markets for these types of products mature, the products’ simplicity makes it difficult for companies to continue to differentiate their products along to continue to differentiate one product from another along functional dimensions – there are too few from which to chose. This in effect forces manufacturers to differentiate their products along an emotional dimension in order to build and maintain brand loyalty. For these companies, emotion-based messages skills are necessary for survival.

At the other end of the spectrum we find companies in industries that produce highly functional items such as medical devices, financial services, and computer ad software tools – all products that must satisfy 50 to 150 desired outcomes or more. Such products can be differentiated along many functional dimensions, and customers who buy and use such products rarely use them to get emotional jobs done.

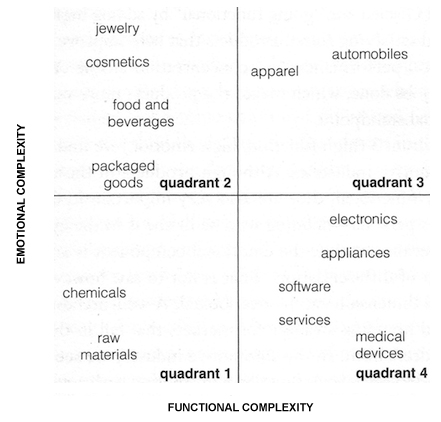

Let’s examine the four quadrants and understand how products can be categorized based on their combination of functional and emotional characteristics.

Quadrant 1 (low function, low emotion)

Industries involved in the production of raw material and chemicals. Since products in these industries have very few functional outcomes or emotional jobs associated with them, companies in this quadrant are better of positioning and differentiating their products along another dimensions altogether, such as service or cost.

Quadrant 2 (low function, high emotion)

Cosmetics, food and beverage, and packaged-goods industries. These industries spend considerable time differentiating along emotional dimensions – as well they should, since many of these products have limited function. Much is to be gained, however, by trying to make these products more functional. It not only adds a new avenue for differentiation, but it also makes the product more valuable to the user. Functional foods have become a product category in and off themselves.

Quadrant 3 (high function, high emotion)

Apparel and automotive industries. Although products in these industries are highly functional, they are also very important in defining the customer’s persona – defining who he or she is in the eyes of other people. Because of this, the emotional component is an important dimension of differentiation. That is not to say, however, that the functional dimension can be overlooked. A well-orchestrated messaging and branding strategy for markets that fall in this quadrant should address both.

Quadrant 4 (high function, low emotion)

Electronics, software, services, and medical-device industries. The focus here needs to be on function, as these products have little emotional appeal. Here, the challenge is to figure out along which functional dimensions a product should be differentiated. Then too, once a company can successfully address underserved outcomes in the functional realm, it may be able to look for value in the emotional realm without suffering Motorola’s fate. Apple, for example, is well known for adding an emotional dimension to its products, but only after making them highly functional.

So what can we learn from all of this?

An emotional messaging strategy that works well for marketing giants in low-function markets will not work in high-function markets. Different markets require different messaging strategies.

SEE ALSO:

– Best Practice: Uncovering Unmet Customer Needs

– Rethinking Innovation: Can Marketing Help?

– A New Marketing Era: Focus on Jobs and Outcomes

– Outcome-Based Segmentation

– How to Map a Customer Job